- Home

- Sara Jafari

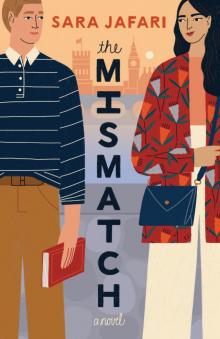

The Mismatch

The Mismatch Read online

The Mismatch is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2021 by Sara Jafari

Book club guide copyright © 2021 by Penguin Random House LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Dell, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Originally published in the United Kingdom by Arrow, an imprint of Cornerstone, in 2021. Cornerstone is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies.

Dell and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

ISBN 9781984820020

Ebook ISBN 9781984820013

randomhousebooks.com

randomhousebookclub.com

Book design by Alexis Capitini, adapted for ebook

Cover design and illustration: Abbey Lossing

ep_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1: Soraya

Chapter 2: Soraya

Chapter 3: Neda

Chapter 4: Soraya

Chapter 5: Soraya

Chapter 6: Soraya

Chapter 7: Neda

Chapter 8: Soraya

Chapter 9: Soraya

Chapter 10: Neda

Chapter 11: Soraya

Chapter 12: Soraya

Chapter 13: Neda

Chapter 14: Soraya

Chapter 15: Soraya

Chapter 16: Soraya

Chapter 17: Neda

Chapter 18: Soraya

Chapter 19: Soraya

Chapter 20: Neda

Chapter 21: Neda

Chapter 22: Soraya

Chapter 23: Soraya

Chapter 24: Neda

Chapter 25: Soraya

Chapter 26: Soraya

Chapter 27: Soraya

Chapter 28: Neda

Chapter 29: Neda

Chapter 30: Soraya

Chapter 31: Soraya

Part Two

Chapter 32: Neda

Chapter 33: Soraya

Chapter 34: Soraya

Chapter 35: Soraya

Chapter 36: Neda

Chapter 37: Neda

Chapter 38: Soraya

Chapter 39: Soraya

Chapter 40: Neda

Chapter 41: Neda

Chapter 42: Soraya

Chapter 43: Soraya

Chapter 44: Neda

Chapter 45: Soraya

Chapter 46: Neda

Chapter 47: Neda

Chapter 48: Soraya

Chapter 49: Neda

Chapter 50: Neda

Chapter 51: Soraya

Part: Three

Chapter 52: Soraya

Chapter 53: Soraya

Chapter 54: Soraya

Chapter 55: Neda

Chapter 56: Soraya

Chapter 57: Soraya

Chapter 58: Soraya

Epilogue

Dedication

Acknowledgments

A Book Club Guide

About the Author

Neda wondered whether other people noticed when their families fell apart or if, like her, it caught them by surprise. Time and time again, after everything they had been through, and just when she felt able to exhale, loosen her shoulders, a new problem would arise, the ground shifting beneath her once more.

Her daughter’s words echoed in her ears.

The cars ahead of her blurred into one. She pulled over to the side of the road, without indicating and without checking her mirrors, car tires screeching in the process. They jolted forward when she slammed on the brakes.

Laleh had spoken and there was no going back now.

“How could this have happened?” Neda said through gritted teeth.

“I don’t…” Laleh whispered before breathing out unsteadily, tears running down her face.

A bus honked at them for stopping in the bus lane.

“You don’t know?” Neda’s tone was mocking.

“Do you hate me?”

“You’re a stupid, stupid girl.” Neda’s head was in her hands as she came to terms with her own worst childhood fear being realized by her daughter. The mood in the car shifted from hostile to fearful. “What do we do?” Neda said to herself.

Laleh kept her head bowed while Neda turned and stared at her. She was ashamed of her daughter, of course, but that did not mean she wanted anything bad to happen to her. Thinking of how Hossein would react made Neda turn pale. What an Iranian man would do upon finding out his seventeen-year-old daughter had transgressed to such a degree…

“How could you?” Neda whispered. She gripped her daughter by the shoulders, fingernails digging into her flesh.

They were unaware of the cars still whizzing past them. Some drivers shouted profanities. It was all background noise. Inconsequential in comparison to what was to come.

Neda removed her hands from Laleh and folded them on top of each other in her lap.

“What should I do?” her daughter asked.

Neda had always provided her children with guidance, but how could she help Laleh now?

She made a promise to herself that she would do better for the others. But for her eldest daughter it was too late.

“You must never tell your dad.” Neda spoke sharply then softened her tone. “He would kill you.”

“So what do I do?”

“You have to leave.”

When people asked Soraya how many people she had slept with the number varied depending on her mood.

Ten.

Six.

Three.

Twelve.

Or sometimes she might say nothing at all, instead suggesting she didn’t want to talk about it, which made them think the number was at the higher end. Such inquiries focused on her level of experience, worked on the assumption that she must have some, so she didn’t feel bad about lying. She knew she couldn’t expose the extent of her inexperience; to be different was to be noticed. She didn’t want to be noticed. Not in that way.

Soraya Nazari was twenty-one years old and had never been kissed.

At school and sixth form it was clear she was a virgin; everyone knew she wasn’t allowed a boyfriend; her family’s strictness was recognized. She wore unflattering clothes that showed no skin, revealed no curve, her shape left to the imagination, though she doubted anyone bothered to imagine it. She didn’t go to parties, or the final year prom. She wasn’t allowed.

At university, away from home, in London, no one knew her past. The only exception was her closest friend, Oliver. But his predicament was akin to hers, their mutual understanding unspoken and concrete.

Perhaps suspecting moving away from home would lead to haram acts, a week before Soraya left, three years ago now, her mum took her for a walk on Wor

thing Beach.

There was only an elderly couple walking along the seafront at a distance. The wind was lashing hard enough almost to blow her mum’s silk hijab away. Despite the wind though, the sky was clear.

“I need to talk to you about something, and you need to take what I say seriously,” her mum said.

Soraya could already feel the weight of what her mum wanted to say, and longed to escape such a conversation.

“Boys will try and get you alone when you go away. They may try and do things with you.” Despite her mum’s grave tone, Soraya rolled her eyes. “Don’t let them do that. They only have one thing on their mind. Doing it would ruin your life. And remember”—she paused for dramatic effect—“God is watching.”

“I know,” Soraya said. “Nothing will happen. I’m smart enough, don’t worry.”

At least she hadn’t lied to her mother: nothing did happen at university.

* * *

—

Soraya carefully considered everything she did; she thought and rethought the consequences of her actions. It was not as simple as once she moved away from home to university, all of the teachings from her younger years about the importance of morals and purity were discarded. She was gradual in her approach; gradual in doing the things she’d longed to do when she was growing up.

In first year, she drank for the first time, took drugs, and went to parties.

In second year, she wore short skirts and dresses without tights.

In third year, she attempted to talk to boys. But unlike the other rules she broke, this one was difficult to do with reckless abandon. Muslim guilt was a funny thing. It came when she least expected it.

It was impossible to disentangle her guilt at disobeying God from the guilt of disobeying her parents. The weight of it sat limp and heavy inside her.

Because she was a girl the rules enforced upon her all related to her sexuality, specifically with the aim of preserving her virginity. Going to parties and drinking alcohol led to a loosening of inhibitions (supposedly), which would (supposedly) then lead to premarital sex, known as zina. A shameful deed, an evil, which leads to other evils.

But with more and more time spent away from home, she wondered why sex was so evil. Why disobeying her family was so abhorrent. Why so much focus in her family’s preaching was on controlling her, rather than on her being a good and just person.

She longed to think freely, and not overanalyze her every decision.

Such thoughts, while troubling in the dead of night when she was unable to sleep, were unimportant now. It was a week before her graduation, and she had to either find a job or move back home with her parents. While she was once, three years ago, like a rabbit released into the wild, there was now the imminent threat of having to return to the same small hutch. A hutch she had outgrown.

* * *

—

“Why do you want to work for Purple B? Why marketing? Why data protection?”

It was Soraya’s first graduate job interview, but she was fairly certain they were meant to ask only one question at a time.

She laughed nervously to buy herself some time. She looked around the bland meeting room, hoping inspiration would spark, but with its glass walls it was sterile apart from the rectangular table and the chairs surrounding it.

“Um, well, I have a keen interest in social media, and I know how to use all the channels really well. You’re a company that prides yourself on keeping people and companies safe, and data protection is incredibly important, especially today, with all the scandals in the news…” She wasn’t actually sure if there were any scandals in the news currently but gave them a “you know” look as though this was obvious.

The two interviewers nodded slightly. The younger of them was a portly man who gave her a reassuring smile, while the bald-headed, older man was impassive.

Their team was small, contained within one medium-size office, and the meeting room she was in was akin to a fish tank. She didn’t dare look at the workers outside for fear that they were looking in.

“How do you think you can get people to subscribe? There’s so much free content online everywhere these days, how can you encourage paid subscribers?” the older man asked.

Well, Soraya thought, aren’t you meant to teach me that? Somehow this was not a question her English literature degree had prepared her for.

She knew how painful it was to attempt to read Ulysses in just one week, about the layers of symbolism in A Doll’s House, could compare the different portrayals of misers in seventeenth-century literature, even knew Ronald Knox’s ten commandments of detective fiction by heart. But all of that was useless to her here.

“Through social media…” Soraya began but wasn’t quite sure how to finish. They looked at her, waiting. “And online engagement…” These buzzwords meant nothing to her.

After four more similarly painful interactions, they thanked her and said they would be in touch in the coming weeks.

“Before you go, I have to ask,” the portly man began, “where are you from?”

Her smile faltered for just a second.

“Oh, I’m from Brighton,” she said.

“Really?” he said, leaning forward. The other man was gathering papers, ignoring the conversation around him.

“Well, some people say I have a bit of a Northern accent because my family used to live in Liverpool, so I guess I might have a Northern twang…”

“I meant more your name. Soraya Nazari.” He said it with the emphasis on the wrong letters, putting his Western spin on it. “It’s different, rather…exotic.”

There was a short silence.

How many times in recent years had Soraya been called “exotic”? Too many. And yet, she couldn’t remember anyone calling her that back home when she was younger. She remembered frequently being called a “Paki” however.

At first, she didn’t mind the term “exotic,” preferred it to racial slurs anyway. But it was only when she told her friend Priya this and Priya’s immediate reaction was to spit out “We’re not fucking fruit!” that Soraya realized it wasn’t a good thing, but rather an act of othering.

A dictionary definition of “exotic” is

Introduced from another country: not native to the place where found.

Foreign, alien.

Strikingly, excitingly, or mysteriously different or unusual.

Of or relating to striptease.

So, with this definition in mind, it stung to be called “exotic.” But she was desperate; this was the first graduate interview she had been invited to, and she had applied for jobs all summer, so she pretended to be unbothered by his comment.

“Ah, yes, my family came over from Iran,” she said. “But I’ve only been a few times.”

“Anyway,” the older man said, standing, perhaps saving his colleague from making any further remarks. “Thank you, Soraya, for coming in.”

She shook their hands in turn, remembering to use a firm grasp as though they’d hire her based on her above-par handshake despite the interview being a flop.

As she waited for the lift—an awkward experience in which she pretended she couldn’t see everyone working around her as there was no corridor, the office being just one room—she felt an unfounded sense of hope. Maybe she didn’t do so badly, she thought. Perhaps it was like in exams when she thought she did terribly, but in reality got a respectable B.

When the lift eventually arrived Soraya quickly walked in and pressed the close button. She looked at herself in the mirror, straightening her Zara trouser suit. She had red lipstick smudged on her front teeth, which she wiped off quickly with her clammy forefinger, hoping they hadn’t noticed.

Exiting the building onto Old Street, she was met by an onslaught of workers rushing back to their offices post-lunch. As she walked

towards the station, she became increasingly irritated: by the strappy kitten heels she’d decided to wear, by London’s uneven pavements, by the people hovering behind her, trying to get around her. In London, you couldn’t just walk at your own pace to your destination. The streets were too overcrowded and you were either slowed down by those in front or, like now, bothered by the people breathing down your neck. There was no space simply to enjoy a leisurely walk. She felt the urge to stop, quite suddenly, and create a human domino effect of people piling into each other and toppling over.

Ultimately, though, she was irritated because she had nowhere to be, no purpose, and she had never had this feeling before. Education had always been at the forefront of her mind, and there was always something she should be doing—an essay to be written, a book to be read, notes to be revised.

Now her future lay ahead of her, with no plan, no time line of what was to come, and she was falling face-first, ungracefully, into adulthood.

The Richard Hoggart Building stood tall and not quite proud. The building was newly renovated, its exterior now featuring a gleaming white entryway with gold accents. By the front was no longer a shabby car park but instead landscaped grounds with benches, the perfect place for pregraduation photos. Families stood with their phones out, encouraging their soon-to-be graduates to pose by the grand university building. It was strange, Soraya thought, that people she had once seen snort MD and pee out of open windows (girls included) were now in suits and heels with their families. Everyone looked older since their final exams in May, three months ago now. Many stayed in their London houses over the summer, but she had seen only a handful of people from her course since university had ended.

The Mismatch

The Mismatch